Vultures provide vital ecosystem services and as they are adept at locating carrion from considerable distances, it is widely considered by local people in southern Africa that they possess highly developed clairvoyant powers.

Possession of a vulture’s head is widely believed to induce clairvoyant dreams that predict impending danger, the results of a gambling venture, or enhance the tracking of animals during an upcoming hunt. To reach a clairvoyant state and to gain insight on various matters on behalf of a client, n‘angas may smoke dried vulture brains mixed with herbs, while an infusion of vulture brains and herbs may also be administered directly to a client to induce a similar state. Ndebele isangomas and isanuse may wear vulture bones on their girdles to enhance their own powers, while the heart, feet and feathers are also much sought after for various other physico-medicinal purposes. Vulture body parts are thus often harvested for sale in traditional markets across the region.

The accessibility of modern pesticides and other poisons, along with heightened economic stress, has led to a marked increase in deliberate poisoning incidents, which often result in mass vulture mortalities and inadvertently put at risk those people who handle, ingest or inhale products derived from these poisoned birds. This unsustainable practice is noticeably more prevalent prior to elections, major examinations, horse races, football matches, or other high profile sports events, when the decapitated and dismembered remains of many vultures may be discovered at the poisoning site. The fact that circling vultures draw the attention of authorities to illegal poaching activities has now exacerbated the problem, as these birds may often be directly targeted for this reason, with body parts also removed opportunistically for sale.

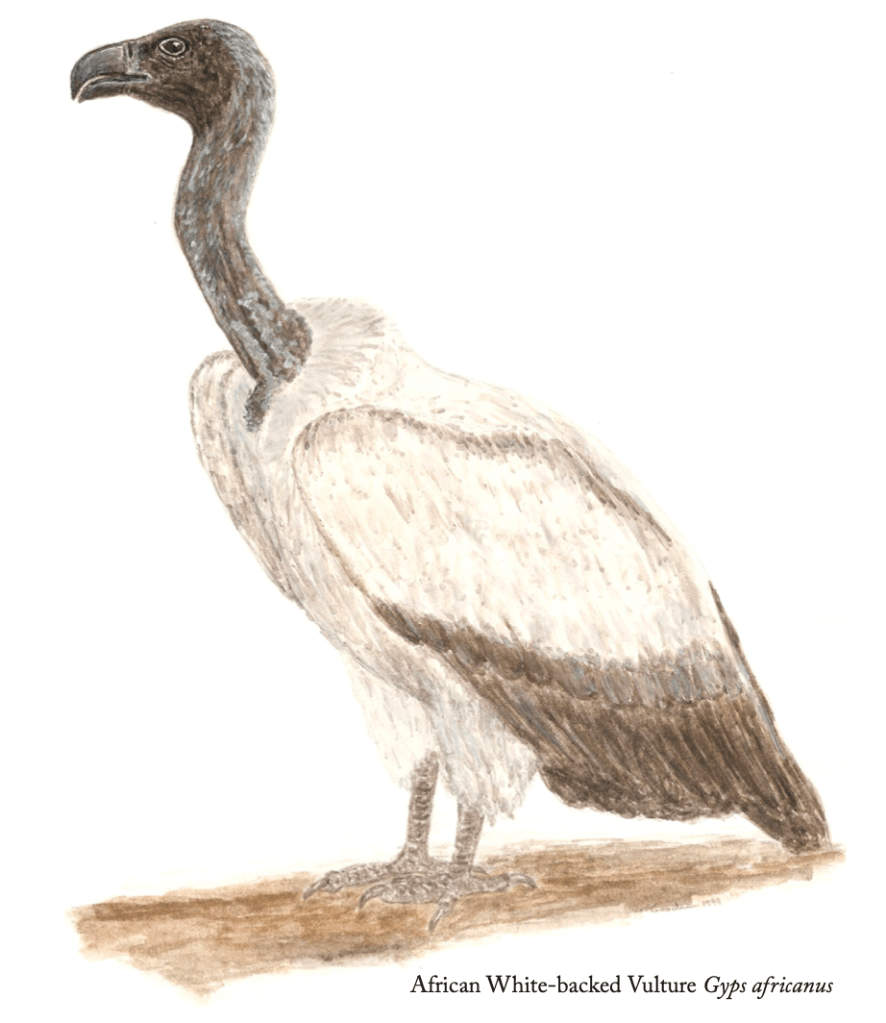

The Lapped-faced Vulture Torgos tracheliotus, Hooded Vulture Necrosyrtes monachus, White-headed Vulture Trigonoceps occipitalis, African White-backed Vulture Gyps africanus and Cape Griffon Gyps coprotheres (pictured) are species most likely to be encountered in the region.

Local names for vultures in Zimbabwe:

Gora, Wanga – Shona (all dialects)

amaNqe, iLingqge – Ndebele/Kalanga

Gola – Nambya

LeHaka – Sotho

Itanga – Venda

Khoti – Shangaan

Nkubi – baTonga

Information for this section was gathered from contributors as well as references below.

References:

Bozongwana, W. (1983). Ndebele religion and customs (1st ed.). Mambo Press, Gweru, Zimbabwe.

Mundy, P, Butchart, D, Ledger, J & Piper, S. (1992). The Vultures of Africa, Russel Friedman Books, Halfway House, South Africa.

Additional information pertaining to other regions of Africa is included below.

Similar, but perhaps even more expanded cultural beliefs regarding vultures are prevalent in West Africa, and while these birds are apparently afforded some traditional protection in Burkina Faso, a number of practices continue to drive the illegal trade in vultures and their body parts across other parts of the region.

Wildlife traders in Nigeria are mostly women of the Islamic faith from the Yoruba ethnic group, domiciled mainly in the southwestern areas of that country, as well as Benin, Togo, Sierra Leone and Ghana. This trading practice has been culturally preserved through generations, with certain religious beliefs acting as an additional driver. The Hooded Vulture and the Rüppell’s Griffon Gyps rueppelli, known as Igun and Akala respectively in the Yoruba language, are two of the most widely used raptors for belief-based purposes in southwestern Nigeria. As the harvesting of vultures for food is is generally considered a taboo by the Yoruba, collection mainly takes place for the purposes of a wide range of medicinal, spiritual, and ritual practices, including treatment of mental illness, epilepsy, strokes, safe birthing in women, spiritual protection against evil spirits and witchcraft, good fortune, as well as enhancement of clairvoyant powers as in southern Africa.

These cultural beliefs have evolved from a combination of entrenched religious beliefs and myths based on the characteristics of these birds, and indeed some buyers are motivated by ‘the doctrine of signatures’ in which the morphology or ‘signatures’of animals determine their choice of product. As such, the relatively long-life span of a vulture is believed to confer an increased life span for consumers of vulture products, while their habit of feeding on the carcasses of other animals confers additional power to the consumer. Perceived benefits could include increased business success, spiritual power, or good fortune, and are based largely on the ritualistic and symbolic power of the vulture rather than the medicinal benefits mentioned. This is despite the old local adage ‘we do not kill the vulture, we do not eat the vulture and we do not use the vulture as sacrifice to the gods to remedy human destiny’, a social norm which seems to have been largely lost and needs to be re-established.

Also of interest is the fact that ancient Egyptians revered vultures, and associated them with the two deities of femininity and motherhood, Nekhbet and Mut, both represented in vulture form with outstretched wings to symbolise maternal protectiveness and love.

Additional References:

Awoyemi, SM, Thomas-Walters, L, Anthony, BP, Vyas, D, Buij, R & Amusa, TO. (2022). Culture and the illegal trade in vultures in southwestern Nigeria: conundrums and recommendations. Vulture News 83: 18-31.

Cocker, M & Tipling, D. (2013). Birds and People, Jonathan Cape, London, England.

For more information on the species mentioned here visit:

https://ebird.org/species/lafvul1?siteLanguage=en_AU

http://datazone.birdlife.org/species/factsheet/lappet-faced-vulture-torgos-tracheliotos

https://ebird.org/species/hoovul1/L6227491

http://datazone.birdlife.org/species/factsheet/hooded-vulture-necrosyrtes-monachus

https://ebird.org/species/whhvul1/RW

http://datazone.birdlife.org/species/factsheet/white-headed-vulture-trigonoceps-occipitalis

https://ebird.org/species/whbvul1

http://datazone.birdlife.org/species/factsheet/white-backed-vulture-gyps-africanus

https://ebird.org/species/capgri1?siteLanguage=en_AU

http://datazone.birdlife.org/species/factsheet/cape-vulture-gyps-coprotheres

https://ebird.org/species/ruegri1?siteLanguage=en_AU

http://datazone.birdlife.org/species/factsheet/ruppells-vulture-gyps-rueppelli